domingo, 31 de diciembre de 2006

Saieh ignora a Bofill

| El martes pasado, Álvaro Saieh reunió a medio millar de empleados de Copesa en el Hotel Hyatt. Su objetivo era anunciarles que dejaba la presidencia de la compañía en manos de su hijo, Jorge Andrés Saieh. La jornada fue emotiva, hubo una presentación en PowerPoint y muchos brindis por los éxitos que ha tenido el grupo en su batalla mediática y comercial contra “El Mercurio”. Pero también hubo un gran olvidado: en su largo discurso, Saieh no hizo ninguna mención al director de “La Tercera”, Cristián Bofill, considerado el gran artífice del éxito periodístico del diario. Algunos atribuyeron el desaire a una cuenta pendiente de Saieh con su director estrella, y otros lo achacaron simplemente al estilo poco protocolar del empresario; pero el incidente fue comentario obligado en los medios del holding durante toda la semana. Pese a la omisión de su jefe, Bofill tuvo ocasión de probar in situ su apego por la noticia: en mitad de la ceremonia recibió un llamado en su celular avisándole de la expulsión de Jorge Schaulsohn del PPD, ante lo cual no dudó en levantarse de la mesa que ocupaba y partir a trabajar junto a algunos de sus colaboradores. |

viernes, 29 de diciembre de 2006

¡Feliz 007! Un año con licencia para todo

junto a mi hijo, el pequeño duende que baila (requieres flash player) .

jueves, 28 de diciembre de 2006

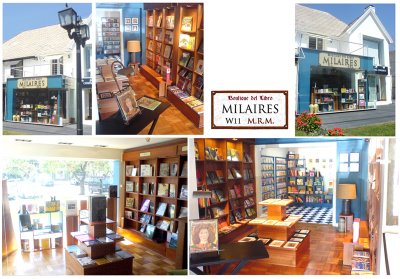

Milaires

Vale la pena darse una vuelta por esta nueva librería de Alonso de Córdova 2448 (entre Francisco de Aguirre y Vitacura). Aclaro de entrada que Milaires es de mi amigo Mile Mavroski y su chica, la Clara. Llegaron no hace mucho de Londres con la idea de armar una "boutique del libro" bajo el brazo. Unas semanas atrás conocí la tienda y me gustó mucho. El lugar es pequeño pero cómodo. Milaires se especializa en accesorios y libros únicos, sobre todo de diseño gráfico, industrial, arte y arquitectura, pero además tiene una sección infantil la raja, que te hace flipar con esos libros de antaño, con tapas de cuero o que los abres y saltan las figuras tridimensionales de papel. Pura nostalgia para uno o para compartirla con los hijos. Además, puedes pasarte horas viendo apoya libros, pisapapeles, papelería artesanal, postales, cuadernos hechos a mano, lámparas de lectura y otros chiches muy entretenidos.

miércoles, 27 de diciembre de 2006

martes, 26 de diciembre de 2006

Me da un kilo de libros por favor

Como contrapartida, los libros del año según Artemio Lupín, uno que no tuvo velas en este entierro y decidió "meter la cuchara" con el humor que le caracteriza (don Artemio es cierto: los Montos y el Mapu son cosa distinta, no así la historia de sus líderes tras la recuperación democrática en Argentina y Chile. Si se fija bien, tuvieron una influencia gravitante en los círculos del poder y se vincularon estupendamente con el mundo empresarial).

domingo, 24 de diciembre de 2006

martes, 19 de diciembre de 2006

La historia no contada del verdadero cerebro del atentado a Pinochet

A una semana de la muerte del dictador revelamos los aspectos inéditos del rol que le cupo a Rodrigo Rodríguez Otero en la Operación Siglo XX: su infiltración en el mundo militar, su vida en Cuba y su visita a Chile el 7 de septiembre pasado, día en que se conmemoraron 20 años de la emboscada.

Por Miguel Paz / La Nación Domingo (17 de diciembre de 2006)

Parecían estar solos. Sin que nadie supiera que estaban ahí. Igual que aquel domingo de 1986 que estremeció al país cuando corrió la noticia de que el Frente Patriótico Manuel Rodríguez (FPMR) había intentado matar al dictador en la cuesta Las Achupallas del Cajón del Maipo. Veinte años después, en la fría tarde del jueves 7 de septiembre, apenas un puñado de fusileros de la emboscada, ex miembros del FPMR y los padres de los hermanos miristas Rafael y Eduardo Vergara Toledo, asesinados en 1985 en Villa Francia, volvía al lugar para conmemorar la Operación Siglo XX, como se denominó el atentado. Entre ellos estaba Rodrigo Rodríguez Otero, protagonista de un capítulo no contado hasta hoy. Un hombre que viajó especialmente de Europa para encontrarse con su pasado, cuando en el Frente le llamaban “Tarzán”.

Esta es su historia.

EL ENCARGO

La jefatura del FPMR venía analizando la decisión de eliminar al general Augusto Pinochet desde fines de 1984. Por entonces, las protestas masivas del año anterior, más el sostenido aumento de jóvenes interesados en militar en la organización, junto con la llegada al país de oficiales preparados en Cuba y con experiencia en combate en Nicaragua, presentaban un cuadro auspicioso para tamaña idea.

Aun así, la decisión final habría de ser tomada en la cúpula del Partido Comunista y con participación expresa de su comisión militar, dirigida por Guillermo Teillier, y consensuada con la Dirección Nacional (DN) del Frente. Todos concordaban que para dar luz verde a la operación era necesario contar con la mayor cantidad de datos a mano sobre la seguridad y los traslados de Pinochet. Por ello, secretamente, la dirección del Frente decidió encargarle a un joven y fornido militante de la organización el delicado trabajo de investigar la rutina de Pinochet: Rodrigo Rodríguez Otero. Su misión era definir la mejor forma de ajusticiar al general. Tenía 23 años de edad.

AÑOS EN CUBA

Con estudios de ingeniería en la Universidad de La Habana y cursos de lucha irregular, Rodrigo se había convertido en militante del FPMR en Cuba, adonde llegó junto a su familia después del golpe de Estado. En 1975, el matrimonio formado por el director de teatro Orlando Rodríguez y la periodista Marcela Otero Lanzarotti, sobrina del destacado director de “Ercilla” Julio Lanzarotti y hermana del actual embajador de Perú en Chile, Hugo Otero Lanzarotti, se trasladó a vivir a La Habana con sus dos hijos, Rodrigo, el mayor, y Álvaro, el menor.

En La Habana, los Rodríguez-Otero se instalaron en un pequeño departamento de los edificios ubicados detrás de la sede del Comité Central del Partido Comunista cubano.

En esos blocs construidos en los primeros años de la Revolución, donde vivían otras familias de chilenos, los Rodríguez-Otero trabaron amistad con Raúl Pellegrin y Judith Friedman, padres de Raúl, un serio jovencito que llegaría a ser el número dos del FPMR. En esos años, ambas familias estrecharon lazos en cenas a las que solía asistir el abogado comunista Eduardo Contreras.

Por su condición de periodista, la madre de Rodrigo, además, se vinculó al trabajo de prensa que efectuaba el Aparato Chile Informativo. Esta fue una iniciativa creada por la sicóloga Marta Harnecker, pareja de Manuel Barbarroja Piñeiro, líder del Departamento América, para recopilar y reproducir las informaciones sobre lo que estaba pasando en el país. En esas actividades también laboraron Mario Gómez López y el propio Contreras, que se las batía como podía entre estos pesos pesados del periodismo, dice.

Más tarde, tras regresar del exilio en 1983, Marcela destacaría como una de las mejores periodistas del país por su trabajo en la revista “Hoy”, siendo la primera periodista que se atrevió a escribir reportajes denunciando las violaciones de los derechos humanos. La mujer, asimismo, sostuvo una corresponsalía de Prensa Latina en su propia casa hasta el día que murió de cáncer, el 4 de diciembre de 1990.

Mientras los padres de Rodrigo y Álvaro efectuaban labores de apoyo a la oposición chilena desde Cuba, los muchachos se educaban junto a niños cubanos y otros jovencitos chilenos, como su primo Alejandro Otero, que pensaban en crecer pronto para regresar a Chile a botar al dictador.

INFILTRADO

Recibida la orden por parte de la jefatura del FPMR, “Tarzán” se abocó a las tareas de organizar su grupo de forma compartimentada y de conseguir información de inteligencia sobre la vida, las relaciones personales y los traslados de Pinochet. En las primeras semanas de preparación pasó días completos en la Biblioteca Nacional revisando minuciosamente los artículos de prensa que mencionaban al dictador. Pero además se inscribió en un gimnasio del barrio alto frecuentado por oficiales del Ejército y cadetes de la Escuela Militar. Gracias a su capacidad para levantar pesas como si nada y su personalidad canchera, rápidamente se ganó la confianza de los uniformados e incluso compartió departamento con uno de ellos. Por si fuera poco, se afilió a un club de paracaidismo ligado al mundo castrense. Sin saberlo, en conversaciones informales con “Tarzán” los militares le entregaban al “enemigo” información importantísima sobre el general, que luego era chequeada por los grupos de “exploración”.

A éstos les cupo un lugar clave en los largos meses de preparación del atentado. Aparentando ser “parejas de enamorados, vendedores ambulantes, estudiantes de inocente aspecto, mujeres de elegante atuendo y hombres con apariencia de prósperos empresarios”, escriben Patricia Verdugo y Carmen Hertz en “Operación Siglo XX”, estos grupos “realizaron tareas de vigilancia y seguimiento” de Pinochet para fijar sus rutinas.

Finalmente, tras desechar otras opciones de atentados suicidas, el grupo de “Tarzán” propuso hacer explotar el vehículo de Pinochet –al estilo del atentado de ETA a Luis Carrero Blanco en 1973 en España– cuando volviese a Santiago de su residencia de fin de semana en El Melocotón. La idea fue aceptada por el PC y se iniciaron los preparativos.

LA PANADERÍA

Meses antes, en enero de 1986, Rodríguez Otero le habló a su primo Alejandro del atentado y lo incorporó a las tareas de “exploración” en el Cajón del Maipo. Sería el propio Alejandro Otero quien vio que se vendía la panadería que compró con su madre, Alicia, desde la cual se cavó el túnel bajo la ruta.

No obstante los preparativos, el plan fue abortado el 7 de agosto, el día siguiente del descubrimiento de la internación de 70 toneladas de armas del FPMR en Carrizal Bajo.

Uno de los frentistas que estuvo en la panadería recuerda su conversación con Cecilia Magni, la “comandante Tamara”, quien ya estaba al mando de la cuestión logística de la operación. “Ahí me dice tengo una buena noticia, y me da un tremendo reloj; tengo una mala noticia, esto se cierra. Entonces, el ‘Tarzán’ dijo: ya, hagámosle una emboscada. Se demoró poco porque el domingo 31 de agosto ya estaba todo listo en la casa de La Obra”.

Ese día, los 21 fusileros de la Operación Siglo XX, incluido Rodrigo Rodríguez Otero, que figuraba con la chapa de “Jorge”, ya estaban en estado de alerta “combativa” estudiando la operación encerrados con su grupo respectivo en las habitaciones de la Casa de Piedra.

“A las ocho de la tarde de ese domingo nos dimos cuenta que la operación no se hacía”, comenta uno de los fusileros, “y una hora más tarde nos dijeron que se posponía la misión” ¿La razón? En la madrugada del domingo 31, Pinochet bajó de El Melocotón a Santiago junto a su comitiva, ya que el Presidente Jorge Alessandri Rodríguez agonizaba. El comandante Ernesto fue avisado a mediodía, pero recién en la noche pudo confirmar plenamente el hecho: Pinochet no estaba.

La operación se postergó para el siguiente fin de semana. Tras casi una semana aparentando ser misioneros shoenstatianos en la Hostería Carrió, los frentistas regresaron a la Casa de Piedra el jueves 4 de septiembre. Hasta el sábado mantuvieron la rutina asignada y esa noche, por primera vez, pudieron conocer el terreno en que emboscarían a Pinochet al día siguiente. Divididos en pequeños grupos se situaron en el sector ubicando puntos de referencia.

EL ATENTADO

El sonido del teléfono cerca de las 18:20 del domingo cortó el aire de tensa espera en la Casa de Piedra. La ciudadana suiza Isabel Mayoraz alertaba a José Joaquín Valenzuela Levy, el comandante "Ernesto" (ver infografía) que la comitiva del general Pinochet pasaba por San José de Maipo en dirección a Santiago. Desde la ventana del segundo piso de la Hostería Inesita tuvo la vista perfecta para cerciorarse de que estaba en lo correcto.

–¡Vamos! –gritó el comandante Ernesto.

“Marcos, al igual que otros, agarró el bolso repleto con los fusiles, otro una bolsa de supermercado conteniendo granadas”, señala “Rodrigo”, uno de los fusileros. “Tamara estaba en la puerta deseándonos suerte”.

El primer vehículo en salir de la parcela fue la camioneta Toyota Hilux del grupo de retaguardia, seguido por el jeep Land Cruiser comandado por “Enzo”, en que iba el grupo de asalto número 1 y el comandante “Ernesto”. Luego el Nissan Bluebird beige del Grupo de Asalto No2 y finalmente el Peugeot Station con la casa rodante conducido por Milton, que haciendo un mal cálculo golpeó una hoja del portón, hasta que maniobrando pudo salir correctamente.

“Nos bajamos en la zona del Mirador y empezamos a subir, cada uno a su posición establecida. Cruzamos el terraplén de una antigua línea férrea. Cerca había una iglesia evangélica en la que se podía oír que estaban en asamblea”, rememora Rodrigo. “Marcos fue dejando los fusiles de cada uno –estaban marcados– en fila y detrás de él otro compañero iba poniendo en el piso las granadas de mano que traía en la bolsa”, señala.

Para entonces el grupo de contención más los dos de asalto ya estaban en sus posiciones. El de retaguardia esperaba en la Toyota Hilux aguardando el momento en que debería acercarse al Mirador, y el Nissan color beige y la Toyota Landcruiser apuntaban sus narices a Santiago, más abajo del Peugeot.

Rodrigo se parapetó al igual que los demás miembros de los dos grupos de asalto. “Cuando vi la primera baliza, segundos después oigo el primer rafagazo. Ahí abrí fuego”. Se oyeron tiros y explosiones por doquier. El primer automóvil de la comitiva, un Chevrolet Opala conducido por el sargento Córdova se detiene con el chofer muerto en su interior. El Mercedes donde viaja Pinochet que sigue al Opala inicia el retroceso.

“Al lado derecho mío estaba la cola de uno de los Mercedes y enfrente uno de los autos de seguridad”, recuerda Rodrigo. “Cuando lo rafagueo, el tipo por la puerta trasera respondió, vacié el primer cargador y volvió a responder. De reojo podía ver algo como se desarrollaba el combate. Una de las cosas que más me extrañó fue ver a Ernesto y Ramiro disparando de pié”, señala.

“De pronto, del último auto vi salir a uno y explotó un cohete y no lo vi más. Luego vi una pierna botada en el camino y el auto incendiándose. Luego uno de los Mercedes retrocede y Marcos prepara el Law, lo veo gatillar y el cohete no sale. Marcos lo cierra lo vuelve a estirar, dispara y el cohete impacta en una de las ventanas sin hacerle mucho daño. El auto dobla en U y retrocede camino a El Melocotón mientras Daniel le vacía el cargador. Después siento los dos pitazos y emprendemos la retirada”.

Las palabras de “Rodrigo” reflejan lo que alcanzó a ver uno de los milicianos. Es el testimonio de una historia que empezó en 1984 cuando la dirección del FPMR le encomendó organizar la emboscada a Rodrigo Rodríguez Otero, el hombre al que todos llamaban “Tarzán”.

.......................................................

(Recuadro)

“TARZÁN” Y EL FISCAL TORRES

.......................................................Rodrigo Rodríguez Otero también tomó parte de otras operaciones del Frente. Como se detalla en el capítulo VIII del reportaje especial de La Tercera “La historia inédita de los años verde olivo”, el FPMR siempre tuvo en la mira al fiscal militar Fernando Torres Silva, “uno de sus enemigos más aborrecidos (...), a cargo de las investigaciones sobre Carrizal Bajo, el atentado a Pinochet y el secuestro del comandante del Ejército Carlos Carreño”.

En 1987 la división del Frente no impidió que ambas facciones siguieran unidas por la idea de ajusticiar a Torres Silva. A diferencia de lo que señalaba un ex frentista establecido en Europa entrevistado para ese reportaje, no habría sido el FPMR-PC el que llevó a cabo la primera de las “dos frustradas acciones para acabar con la vida del alto oficial”, sino que el Frente Autónomo.

Según un miembro de la “Fuerza Especial”, grupo operativo de elite del FPMR-A, conocido como “La columna fantasma” debido a que era una estructura separada del resto de la organización, dicho intento de matar a Torres Silva habría sido llevado a cabo por "Tarzán" y “El Bigote”.

El 27 de mayo de 1988 cuando la comitiva del fiscal transitaba por una avenida de Providencia, los frentistas a bordo de una moto adosaron una bomba al techo del vehículo Ford en que viajaba Torres pero esta resbaló y no explotó. El hecho desconcertó a los motoristas que se habían cerciorado de la efectividad de la carga explosiva dos veces: la primera en un vehículo que resultó ser del rector de una universidad y la segunda en el auto de un coronel del Ejército, estacionado frente al cine California en Irarrázaval.En su huida, “Tarzán” habría sido herido de bala en un brazo producto del disparo de uno de los guardaespaldas del fiscal militar y El Bigote habría salvado ileso.

Sólo la divina providencia salvó al fiscal Torres del segundo intento de acabar con su vida, ideado por el FPMR-PC y realizado en la segunda mitad de 1988. El periodista Javier Ortega relata en “La historia inédita de los años verde olivo”, que “los frentistas se habían percatado de que cada vez que llegaba a su domicilio, el uniformado bajaba del coche y caminaba unos metros hasta su casa”. Pero “el mismo día en que los hombres encargados de la acción lo aguardaban a metros de su casa, sin embargo, Torres Silva ingresó a su garaje sin bajar del automóvil”.

Meses después, en octubre, “El Bigote” también participaría en la toma del poblado de Los Queñes liderada por los comandantes Raúl Pellegrín y Cecilia Magni, “Rodrigo” y “Tamara”. Nuevamente habría librado con vida. No así los comandantes. El 31 de ese mes sus cuerpos aparecieron flotando en el río Tinguiririca. Habían sido detenidos,

torturados y arrojados al río en estado agónico por los aparatos represivos.Al año siguiente, tras una investigación del Frente sobre los sucesos de Los Queñes habría concluido que “El Bigote” había dado información al “enemigo” sobre la operación. Por ello éste habría sido ajusticiado. Hasta el día de hoy se desconoce su identidad.

......................................................................................(Recuadro)

LOS PROTAGONISTAS DE LA OPERACIÓN SIGLO XX

.......................................................................................

· Grupo de Contención o Unidad 501:

Rodrigo Rodríguez Otero ("Tarzán"), “Jorge” o “Juan Carlos”: Jefe de grupo. Instrucción militar previa en Cuba. Armado con un M-16 y un lanzacohete Law que al ser disparado no funciona.

Cristián Acevedo Mardones, “David”: Tareas de contención. Instrucción militar previa en Cuba. Armado con M-16 y lanzacohete Law. Su disparo es el que impacta en el techo del Chevrolet Opala, patente CU-2985, que lideraba la comitiva.

Héctor Maturana Urzúa, “Axel” o “Patricio": Medidas distractivas vestido de mujer y contención. Armado con M-16.

Víctor Díaz Caro, “Enzo”: Tareas de contención de los motoristas que huyen hacia el retén de Las Vizcachas. En la retirada conduce el jeep Toyota Landcruiser. Instrucción militar previa en Cuba. Armado con fusil SIG.

Héctor Luis Figueroa, “Víctor”: Tareas de contención de los motoristas. Chofer del Datsun Nissan modelo Blue Bird usado en

la retirada. Armado con un M-16.

En poder de “Enzo” y “Víctor” se encontraba un lanzacohete RPG2 (de mucho menor calibre que el Law o el RPG7) que sería utilizado para detener el furgón que lideraba a la comitiva cuando llovía.

Arnaldo Arenas Bejas, “Milton”: Maneja el Peugeot station wagon que cierra el paso a la comitiva, tareas de contención. Armado con M-16.

· Grupo de Asalto No 1 o Unidad 502

José Joaquín Valenzuela Levy, “Ernesto”: Jefe militar de la Operación Siglo XX. Instrucción militar previa en Bulgaria. Porta un M-16 y un lanzacohetes Law.

Julio Guerra Olivares, “Guido”: Segundo jefe del grupo. Considerado uno de los más experimentados, se incorporó al grupo el 4 de septiembre como apoyo. Instrucción militar en Cuba. Armado con un M-16 y lanzacohetes Law.

Adriana Mendoza Candia, “Fabiola”: La única mujer que participó directamente de la emboscada. Tuvo instrucción militar en Cuba. Su arma era un M-16.

“Juan”: Nunca identificado. Portaba un lanzacohetes Law y un M-16.

Lenin Peralta Véliz, “Oscar”: Participa armado de M-16 y granadas.

· Grupo de Asalto No 2 o Unidad 503

Mauricio Hernández Norambuena, “Ramiro”: Jefe del grupo. Instrucción previa en Cuba. Cuenta con un M-16 y un lanzacohetes

Law.

Alexis Soto, “Marcos”: Porta un M-16, un lanzacohetes Law y granadas.

“Fabián”: Se desconoce su identidad. Armado con un fusil M-16 y granadas.

Jorge Mario Angulo, “Pedro”: Instrucción previa en Cuba. Porta un Law, un fusil M-16 y granadas.

“Rodrigo”: Se desconoce su identidad. Porta un fusil M-16 y granadas.

· Grupo Retaguardia o Unidad 504

Mauricio Arenas Bejas, “Joaquín”: Jefe de grupo. Portaba un lanzacohete Law y un fusil M-16.

Juan Moreno Ávila, “Claudio” o “Sacha”: Con instrucción en Cuba. Cuenta con un M-16 y un Law.

Juan Órdenes Narváez, “Daniel”: Porta un M-16.“Javier”: Se desconoce su identidad. Conduce la camioneta Toyota Hi lux. Cuenta con una subametralladora P-25.

“Alejandro”: Se desconoce su identidad. Armado con un M-16.

viernes, 15 de diciembre de 2006

The dictator

Una de las gracias de este texto es que su autor pudo sostener largas conversaciones con Pinochet en distintas ocasiones, además de entrevistarse por separado con Lucía Hiriart (aka Lucy in the sky with diamonds).

Otro aspecto relevante es cómo Anderson logra introducirse en zonas muy profundas de la vida de Pinochet, así como descubre que el general era un hombre que estaba fascinado por la figura de Napoleón, el emperador francés que dominó casi toda Europa en el siglo XVIII.

Según cuenta Anderson, en el salón donde se firmó el acta de constitución de la Junta Militar en 1973, Pinochet había dispuesto una colección de medallas de Napoleón.

El genio militar del pequeño estratega europeo junto a la trágica historia de su muerte en el destierro en la isla Santa Helena y la posterior reivindicación de su rol en la historia, ejercían un irreprimible magnetismo sobre el anciano militar en retiro.

Esas obsesiones –explicaba Anderson en un taller que dictó en 2002 en la Fundación Nuevo Periodismo en Cartagena, Colombia- decían "más de la visión sobre sí mismo y sobre la política de Pinochet, que cualquier tratado sobre su personalidad". En los cuatro encuentros que sostuvo con el general, el periodista descubrió que mucho de lo que había hecho Pinochet: "desde la construcción de su famosa carretera austral hasta el bautizo de sus hijos con nombres de Césares (Augusto y Marco Antonio), revelaba una estrecha relación entre el poder absoluto y sus héroes".

Además, descubrió a "un hombre absorbido por el síndrome del heroísmo que añoraba parecerse a Napoleón".

Paradójicamente -según quien opine: periodistas que cubrieron la detención de Pinochet en Londres o cercanos al militar fallecido- habría sido: una solicitud de Pinochet al gobierno francés para visitar la última morada de Napoleón en París; ó el retrato que le tomaron para la nota en el New Yorker en la suite presidencial del Hotel Dorchester, los hechos que alertaron al juez Baltasar Garzón de que Pinochet estaba en Londres y le permitieron ordenar su detención.

THE DICTATOR

por Jon Lee Anderson

Augusto Pinochet ruled Chile ruthlessly, but he left behind a democracy. Now he wants history’s blessing.

Issue of 1998-10-19

“I was only an aspirante dictator,” General Augusto Pinochet said—a candidate for dictator. “I’ve always been a very studious man, not an outstanding student, but I read a lot, especially history. And history teaches you that dictators never end up well.” He said this with an ironic smile.

Pinochet’s famously stern public countenance has been softened by the passage of time. He smiles more than he scowls now, and the sinister dark glasses that he used to wear are gone. He looks like someone’s genteel grandfather. His voice is tremulous and hoarse, his carefully parted and combed hair and trim mustache are white. He has a potbelly, wears a hearing aid, and shuffles uncertainly. A conservative business suit and a tie accented discreetly with a pearl pin have replaced his military uniform.

Some things haven’t changed, though. Pinochet’s expression remains inscrutable. His pale-blue eyes are small and set in a wide, bullish face, and his stare is coldly foxy. The many lines around his eyes come from his smile, which appears suddenly but evaporates just as quickly. And his views don’t seem to have shifted much. “Lamentably,” he says, “almost everyone in the world today is a Marxist—even if they don’t know it themselves. They continue to have Marxist ideas.”

Pinochet is almost eighty-three years old, and justifying his actions, clarifying his place in history, is on his mind. He explained to me why he wasn’t a real dictator as we sat at a large table in the dining room of a house he uses as an office, just around the corner from his former Presidential residence, in Las Condes, a tony Santiago neighborhood. Security agents with walkie-talkies stood watch on the street in front and roamed through the adjacent rooms and the garden, their weapons bulging under their jackets. Two of Pinochet’s aides, one of them a colonel on active duty, sat at the table with us. They took notes and taped our conversation. The people around Pinochet don’t like him to talk to journalists, but his daughter Lucía had encouraged him to see me, because she thinks that if people understand her father better he will be maligned less. She had warned me that he is brusque, and asked me not to upset him by bringing up the topic of human rights. There are several civil and criminal cases pending against him having to do with torture and murder.

Pinochet shook my hand when he walked into the room, but he didn’t look me in the eye, and when he sat down he stared fixedly at his daughter. Lucía, a woman in her early fifties with her father’s wide cheekbones, had told me that he was affable in private, and had a sense of humor, so I said that I was grateful that he had come, especially since I understood that he was “terrified” of journalists. That made him laugh, and then he looked at me. He wasn’t terrified, he said. It was just that journalists always twisted his words.

Pinochet explained that he had avoided the historical pitfall of dictators because he had never wielded absolute power. At the beginning, he and three other generals, the commanders of the branches of the armed forces, had made up a junta. “In time,” he said, “I became the one who led, because the thing led by four doesn’t work. You’re giving orders here, the other there, the other over there—it’s nothing, nothing. It doesn’t advance! That’s why I was chosen.” Then he had tackled Chile’s constitution, ushering through changes that, among other things, legitimatized his de facto rule by making him the country’s President. The old constitution had been a nuisance. “It tied one up! How can you let yourself be tied up? You have to be able to set the goalposts to be able to act! You can’t have a field where you don’t know where you’re shooting from. So I set the goalposts.”

Augusto Pinochet, all quibbling about definitions aside, is that rarest of creatures, a successful former dictator. According to Chilean opinion polls, roughly a quarter of his fellow-citizens revere him. He has few modern parallels, except perhaps Francisco Franco. (Pinochet was the only foreign head of state to attend Franco’s funeral, in 1975. Ferdinand Marcos sent his wife, Imelda.) Like Franco, Pinochet is an ultra-conservative Catholic nationalist, a military officer with an unremarkable personality who suddenly rose to prominence. Both men imposed their power through violence, and used security forces to maintain it. And, over time, both transformed their societies and built strong modern economies. Pinochet knows that he is frequently compared to Franco, and he is cagey about the analogy. “There is an appropriate leader for each country,” he said guardedly. “Franco was necessary for Spain.”

Pinochet was born in 1915 in the port city of Valparaíso. His father was an easygoing customs agent who hoped that his son would study medicine, but Augusto wanted to become a soldier, and his mother backed his decision. He entered the military academy in 1933, at the age of seventeen. His father died when he was still a young man, but his mother lived until a few years ago, and remained a strong influence in his life until the end. In 1943, he married another strong woman, Lucía Hiriart, the nineteen-year-old daughter of a former senator and government minister. When I met her in Santiago, Lucía Hiriart de Pinochet, a gracious woman in her early seventies, confessed that, as a politician’s daughter, she had found the “subjection” of her husband within the military hierarchy hard to take, and that she had urged him to strive for higher office. “When we discussed his future,” Mrs. Pinochet said, “he said he’d like one day to be Commander-in-Chief. I told him he could get to be Minister of Defense.”

Pinochet climbed up through the officers’ ranks, and in 1971 he was made commander general of the Army’s Santiago garrison. He was by then the author of several books on military geography and on geopolitics. In August, 1973, Salvador Allende, who had become President three years earlier, appointed him Commander-in-Chief of the Chilean Army. Mrs. Pinochet says she couldn’t believe it when her husband told her the news; she thought he was joking. Then, less than three weeks later, the Army staged a coup and Allende killed himself during the attack on La Moneda, the Presidential palace. Her husband would rule Chile, and she would become the First Lady. “My husband had taught me that in a normal career he’d get to be colonel. Anything above would be good fortune and a bit of luck. He became a general because of politics. They call me messianic for saying so, but I believe it was divine Providence that he got to be President.”

He stayed in power for seventeen years. Upward of three thousand people were killed or “disappeared” while he was in office, and tens of thousands more were imprisoned or fled into exile. The new constitution, which was passed in 1980, gave Pinochet an eight-year term as President, but he was so confident of his popularity that in 1988 he held a referendum proposing that his tenure be extended for another eight years. To his surprise he lost, and stepped down from office two years later. A civilian, democratic government was reëstablished, and a Christian Democrat was elected President. Next year is an election year, and the man widely tipped as the winner, Ricardo Lagos, is a former Allende aide and a Socialist.

The country that the new democratic leaders inherited is prosperous, forward-looking. Santiago, the capital city—where one in every three Chileans now live—sprawls in a fertile bowl of land beneath the Andean cordillera, its air amber-colored with smog, the surrounding snowcapped mountains no longer visible most days. Blue- and black-tinted glass-and-marble office blocks are displacing the villas that used to make up the city’s poshest neighborhoods; vineyards are being plowed up to make way for shopping malls and American-style subdivisions. At the intersections of the traffic-clogged roads, huge billboards advertise credit cards, cell phones, and laptop computers. Santiago is a Latin-American beachhead of the thrusting, free-market ethos that transforms urban areas everywhere into mosaics of industrial parks, freeways, office complexes, and suburban sprawl. In this new Chile, the modern, fortresslike American Embassy enjoys a prominent position in a walled compound situated between the Mapocho River—an odoriferous gray flow of water that bisects Santiago—and a shining outcrop of office blocks and hotels known locally as Sanhattan.

“All of this is new. All of it! What was here before . . . was chalets, bungalows. It was beautiful, but it was . . . something different,” General Julio Canessa says. “And all of this was done by the horrible Pinochet.” Canessa is being theatrically sarcastic. He believes that Pinochet suffers from the same unfair criticism that taints Franco’s place in history. “If it hadn’t been for Franco,” Canessa says, “Spain would still be part of Africa.”

Chile’s vaunted economic miracle was brought about by the so-called Chicago Boys, a group of Chilean disciples of the American economist Milton Friedman, who were given free reign to put their theories into practice in the mid-seventies. They encouraged generous incentives for foreign investors and the privatization of businesses that the Marxist Allende had nationalized. This resulted in an average annual economic growth rate of seven per cent for the past fourteen years, a rate three times the over-all Latin-American average. A recent United Nations study of life expectancy, salaries, access to health services, and educational standards rated Chile higher than any other Latin-American country.

This performance brought Augusto Pinochet many admirers among conservatives, including Margaret Thatcher, who sent an aide to Chile to spend six months studying Pinochet’s economic reforms before she embarked on her own in Britain. During his annual trips to London, Pinochet says, he always sends Thatcher flowers and a box of chocolates, and whenever possible they meet for tea. Another admirer is the Russian Presidential aspirant Aleksandr Lebed. Lucía Pinochet showed me a fax she’d just received from an organization in Moscow calling itself Pinochet for Russia. Its members were soliciting books and other materials for their Pinochet archive. Lucía has privately published a large coffee-table book of photographs of her father. It includes a picture of the General on a visit to Madame Tussaud’s wax museum, in London. He is standing in front of the figure of Lenin, wagging his finger at the founder of the Soviet Union in what appears to be a gesture of gleeful admonishment. When I asked Pinochet what it was he had “told” Lenin, he cackled, “I told him, ‘You were wrong, sir! You were wrong.’ ”

Lucía Pinochet, who is the closest to her father of his five children, gave me a version of recent history that I was to hear many times from the Chileans who call themselves Pinochetistas. She explained that the coup against Allende had been necessary because the country was being turned into “another Cuba.” If the armed forces had not stepped in, a bloody civil war would have been inevitable. But she fears that young Chileans have taken for granted the stability and prosperity her father brought to their country. “They prefer to admire Fidel Castro and Che Guevara,” she said sadly. “I’ve learned that you can’t transfer history’s lessons from one generation to another.”

Pinochet’sstrongest support comes from Chilean businessmen and the armed forces. The Chilean Army has a historical museum at the military academy in Santiago, in a gray-green cement building fronted by tall, square colonnades. In one room of the museum there is an exhibit of a small portion of Pinochet’s collection of Napoleonica: great gilt-lettered leatherbound volumes about Napoleon in Spanish and French; bronze busts; and, in pride of place, a framed parchment signed by Napoleon himself. The weathered wooden desk at which the junta was sworn in, on September 11, 1973, after Allende shot himself (with a rifle that had been given to him by Fidel Castro), stands in the gallery outside the Napoleonica room. Nearby is a plaque commemorating the swearing-in, which took place in the lobby below, and set side by side on a damask cloth are bronze life masks of Pinochet and the three other generals who formed the junta. In a second room, more than a thousand silver and gold medals and decorations that were bestowed upon Pinochet during his long career are exhibited behind glass. There are embossed medals from Chiang Kai-shek, King Juan Carlos of Spain, and General Alfredo Stroessner of Paraguay, and a plaque from the World Anti-Communist League.

Curiously, Pinochet’s popularity extends to the People’s Republic of China, which he has visited twice. China is a major client for Chile’s copper exports, and Pinochet has nurtured his relationship with Beijing. “They are very fond of me,” he says. “Because I saw that Chinese Communism was patriotic Communism, not the Communism of Mao. I opened up the doors to Chinese commerce, letting them hold an exposition here, in which they brought everything they had—and they sold everything they brought.” On both his trips to China, Pinochet says, the Chinese treated him with great respect. “The first time they put me in a house, but the last time it was a palace. And I became good friends with General Chen, a warrior who fought in Korea, in Vietnam, and who doesn’t like the Americans very much.” Pinochet shot me a sidelong glance and grinned.

The most ambitious program to preserve Pinochet’s legacy is sponsored by the Augusto Pinochet Foundation, which operates out of a discreet Japanese-style house in Las Condes. The foundation was a surprise birthday gift to Pinochet from a group of former aides, friends, and business leaders. It provides him with a small full-time staff and an office containing a duplicate of his desk in the Presidential palace. The foundation sponsors conferences and holds fund-raisers to provide scholarships for the children of armed-forces personnel. At an event in late August, attended by a hundred or so students from a private university established by Pinochet for military offspring, the director of the foundation, Luis Cortes Villa, a retired general, gave an impassioned pep talk to his young audience. He spoke of the “great sacrifices” that had been made by their mothers and fathers so that the new, modern Chile could be born. Then, pointing to a huge painting of Pinochet in full-dress regalia which dominated a corner of the room, Cortes Villa sang out, in a voice high with feeling, “There he is. He doesn’t walk as he once did, but his ideas are still there, his deeds are there, and we are going to keep on, so that his ideals survive!”

Two hours by car from Santiago, on the Pacific coast, Pablo Neruda’s house, Isla Negra, overlooks a wild, rocky cove. It was here, in mid-September, 1973, as he lay terminally ill with cancer, that the poet was told the news of the coup and of his friend Allende’s death in the attack on La Moneda. Neruda made plans to flee the country, but his condition worsened suddenly and, on September 23rd, he died. Whether or not Neruda’s death was hastened by a broken heart, the poet’s demise became emblematic of the end of intellectual and political freedoms in Chile. As officials of Allende’s government and anyone else suspected of leftist political affiliations were hunted down, tortured, and executed, the death of Neruda hung in the air like a curse.

For many years afterward, Isla Negra remained shuttered and guarded by soldiers, who prevented anyone from approaching it. Now it is open to the public, and no soldiers are in sight. The rambling, single-story beach house is a memorial to Neruda’s many passions: nineteenth-century carved wooden ship’s figureheads, scrimshaw, decorative Belle Époque bottles of colored glass, and primitive masks, and his collection of mounted insects, hummingbirds, and seashells. A half mile away, two mustard-yellow apartment towers, monumental in their concrete ugliness, rise over the hills of the shoreline. The developers wanted to build the apartment blocks even closer to Isla Negra, I was told, but lost the battle after strenuous lobbying efforts by the Neruda Foundation. Isla Negra and the tower blocks coexist in an uneasy stalemate.

In Chile, historical memory is contentious, tarnished, and unstable in its resolution. There is no national consensus about what is valuable and worth keeping about the past and what isn’t. Two competing versions of Chile’s history exist, unreconciled. I had dinner at the elegant Sheraton Hotel in Santiago with a close friend of the Pinochet family. She was a slender, attractive widow of about fifty, whose late husband had been a military officer. When I asked her if he had participated in the coup, she replied emphatically, “Oh yes! He was very active. He even dealt with the prisoners.” She grimaced theatrically. I realized that what she meant was that he had been involved in the roundup of leftist suspects and their subsequent torture and execution. I tried to get her to be more specific. “You’re talking about los fusilamientos—the firing squads?” I asked tentatively. She nodded. “But my husband liked to do things correctamente, and he always secured the help of lawyers.” She was referring to the lawyers who served as prosecutors in the martial-law “war tribunals” set up to try the thousands of people detained following the coup. Even so, I ventured, that kind of duty must have been difficult for him. She nodded, but explained that the area they lived in had been a stronghold of leftist terrorists. “It was a war,” she said. “It was either you or them.”

Salvador Allende’s daughter, Isabel (not the novelist, who is her second cousin), bridles at the term “excesses,” which is the euphemism preferred by Pinochetistas when acknowledging that any abuses occurred during the General’s tenure. “There was slaughter, there was state terrorism!” Allende says. “Many people were murdered, in cold blood, their throats slit, burned to death. These weren’t ‘excesses,’ these were murders that were planned, premeditated, coördinated by the intelligence agencies and state agencies.”

The chaotic, three-year attempt by Salvador Allende to take Chile on the “road to socialism” was opposed by a large portion of the Chilean population. Allende was elected with only a third of the vote, but after he took office he moved quickly, nationalizing the copper mines and other industries, conducting large-scale land reform, and increasing government spending on social-welfare programs. He alienated the armed forces, the private sector, and traditional political parties, including the Christian Democrats. As some members of his Popular Unity coalition government pushed for more radical changes, right-wing militants responded with bombings and killings, and leftists prepared for a civil war. When the coup finally came, not many Chileans were surprised, and many middle-class citizens openly applauded it, although they could not have known that Chile would soon become a proving ground for the grisly anti-Communist dirty wars that were waged in Latin America during the seventies and eighties. If Radovan Karadzic can be given authorship of “ethnic cleansing,” then Augusto Pinochet can probably be credited with adding los desaparecidos—“the disappeared”—to the modern lexicon.

The world saw it all begin on television. First, the daylight bombing, from the air, by British-made Hawker Hunter fighters, of La Moneda, with President Allende still inside. Then came the roundup of thousands of people, who were herded at gunpoint into the huge National Stadium, where they were detained for weeks. Black-hooded informers walked in front of people huddled in the bleachers, pointing out suspected subversives to uniformed officers. Out of sight, in the warren of cubicles of the sports facility, people were tortured and murdered. Firing squads executed hundreds at the stadium and at other places around the country. The musician Víctor Jara was one of the victims, shot to death, his hands broken. People were buried in mine shafts, in unmarked graves, in mass graves yet to be found. A former air-force intelligence agent admitted that bodies were dumped from helicopters over the Pacific Ocean, their bellies slit open so they would sink. Detention camps were set up the length and breadth of Chile. Agents of DINA, the National Directorate of Intelligence, struck against anyone they suspected of being an enemy of the new Chile. The killing became more selective and the techniques of execution were varied as time went on. Allende’s former Foreign Secretary, Orlando Letelier, and his American secretary, Ronnie Moffit, were blown up in Washington, D.C., by a car bomb in 1976. Assassinations continued well into the late nineteen-eighties. In 1985, three Communist Party members were kidnapped and murdered. Their throats were slit, and their bodies were dumped by the roadside.

Not far from Allende’s tomb in the national cemetery in Santiago is a huge wall of white marble inscribed with the names, the ages—ranging from thirteen to almost eighty—and the dates of death or disappearance of the regime’s victims. On either side, stretching away from the great wall of names like wings, are two lower walls, with niches where the bodies are to be placed when they are discovered. Only a few niches are occupied.

Over drinks in her garden, an aristocratic Chilean woman who spends much of her time in Europe and who gives orders to her Alsatian guard dogs in French, said to me, “Chileans are isolated and insular, and, like the Germans, they are incapable of initiative; they need to be told what to do. That is why Pinochet was so good for them.” This analysis was echoed by several other Chileans I met, all of whom cited Chile’s geographical isolation and its hybrid mixture of imported nationalities as key factors in Pinochet’s popularity.

Chile is a narrow, twenty-five-hundred-mile long sliver of a country, cut off from Argentina and Bolivia by the Andes, from Peru by its long northern desert, and bounded on the west by the Pacific Ocean, with only Antarctica to the south. The population ranges from the indigenous Mapuche and Aymara Indian minorities to the mestizo majority—the mixed-blood descendants of the Spanish conquerors—with sizable numbers of the descendants of émigrés from Great Britain, Germany, Serbia, and Croatia in between. All of them have left a mark. Pinochet told me that England is his favorite country—“the ideal place to live”—because of its civility and moderation, its respect for rules. As an example, he pointed to the impeccable driving habits of the British, compared with the “rude” road behavior of his countrymen. Chileans will tell you with pride that they are often called the English of South America.

Chile’s nineteenth-century independence hero and its first President, officially the director supremo, was the half-Irish Bernardo O’Higgins, a cruel and oppressive man whose reputation has undergone a posthumous resurrection. A few years ago, General Pinochet had O’Higgins’ remains moved from the military academy to a site opposite the Presidential palace, where soldiers guard an eternal flame that marks a spot called the Altar of the Fatherland. Some of the soldiers standing watch wear uniforms that are disturbingly similar to those worn by the Nazis. Others look distinctively and unabashedly Prussian: gray tunics with short, stiff collars, spiked helmets, and black leather boots. Between the eighteen-eighties and the nineteen-thirties, Chile’s Army was trained by Prussian officers.

A few blocks beyond La Moneda a grid of pedestrian walkways, peatonales, spreads out for several blocks. One day, at an intersection there, I found a trio of Mapuche Indians—two women and a man with long glossy black braids and necklets of old silver coins—playing native instruments under a banner protesting the planned construction of a hydroelectric dam in their homeland. The banner protested “an affront to the millennium-old Mapuche culture.” Gathered around the Indians in a silent, curious knot were a dozen or so conservatively dressed, white-skinned citizens. To them, clearly, the Mapuches were as exotically foreign as if they had been Tibetans.

Chilean society is unusually insular and socially conservative. Nearly nine years after the country returned to democracy, divorce and abortion are still illegal, homosexuals can be criminally prosecuted, and an official censorship board screens, and occasionally bans, movies. There is much talk of “citizens’ insecurity,” the common euphemism for Santiago’s crime rate, which, according to Pinochetistas, has increased to troubling levels since the General stepped down.

Pinochet’s supporters, of course, have even worse things to say about the government that he replaced in 1973. One of the more common stories—delivered with expressions of shocked repugnance—is that Allende was drunk at the time he died in La Moneda: that an autopsy found his body to be “full of alcohol.” An octogenarian lawyer and former judge, Alfredo del Valle, told me, “Allende was a man without any moral calibre.” When I asked him what he meant, he paused, and then confided that among his friends was an Army officer who, after the coup, led a search of Allende’s home and became “physically sick” by what he saw. “What was there?” I asked. The old lawyer shook his head. “Pornography,” he replied in a disgusted whisper. “Mountains of it—of the worst kind.”

This kind of vilification is, understandably, a source of bitterness to Isabel Allende. She and a sister were part of a small group who stayed at the President’s side in La Moneda on the day of the coup, until he ordered them to leave. A trim woman with short dark hair, Allende received me in the living room of her late father’s home, where her mother, Hortensia, still lives. In an uncanny echo of the concerns of Lucía Pinochet, Allende explained that she had established a Salvador Allende Foundation to “teach the youth of today about my father’s ideals of social justice” and to counteract the misinformation about him propagated during the Pinochet years.

As the twenty-fifth anniversary of the coup drew near this September, a flood of new publications about the period appeared in bookstores. The one that caused the greatest sensation, and became an instant best-seller, was “Secret Interference,” by the Chilean journalist Patricia Verdugo. It includes an annotated transcript of secretly recorded radio conversations between Pinochet and his fellow-officers during the attack on La Moneda. Their voices are clearly audible on a CD that accompanies the book. At one point, Pinochet’s shrill voice can be heard as he speaks to Vice-Admiral Patricio Carvajal, who has just received a message that Allende wants to negotiate.

PINOCHET: Unconditional surrender! No negotiation! Unconditional surrender!

CARVAJAL: Good, understood. Unconditional surrender and he’s taken prisoner, the offer is nothing more than to respect his life, shall we say.

PINOCHET: His life and . . . his physical integrity, and he’ll be immediately dispatched to another place.

CARVAJAL: Understood. Now . . . in other words, the offer to take him out of the country is still maintained.

PINOCHET: The offer to take him out of the country is maintained . . . but the plane falls, old boy, when it’s in flight. (Carvajal laughs.)

A few hours later, after the negotiations have broken down and La Moneda is engulfed in flames, Carvajal relays word to Pinochet that Allende has just been found dead in his office. Worried about the consequences of an Allende funeral, Pinochet is heard debating what to do with the body, and suggests “sticking it in a coffin and putting it on a plane with the family and sending it to Cuba,” or else—the option eventually taken—“burying it secretly” in Chile. At one point, Pinochet wisecracks, “Boy, even dying this guy caused problems!”

Among Pinochetistas, it is an article of faith that Pinochet’s rise to power was, if not an act of God, then at least one of selfless duty, wholly engineered by Chile’s patriotic men in arms. The active American role in aiding and abetting Allende’s downfall has been airbrushed out of their version of history. But in fact, even before Allende took office, in 1970, the Nixon White House authorized a secret C.I.A. destabilization campaign against him. It included funnelling money and arms to right-wing paramilitary groups and plotters within the Chilean armed forces, press disinformation, and unspecified “black operations.” The plan, according to declassified United States government documents, was to make Chile ungovernable under Allende, provoke social chaos, and bring about a military coup. “Make the economy scream,” reads a handwritten memo by Richard Helms, the director of the C.I.A., during a September 15, 1970, meeting with Nixon, Henry Kissinger, and John Mitchell in the White House. A month later, a C.I.A. cable outlined the objectives clearly to the station chief in Santiago: “It is firm and continuing policy that Allende be overthrown by a coup. . . . We are to continue to generate maximum pressure toward this end utilizing every appropriate resource. It is imperative that these actions be implemented clandestinely and securely so that United States Government and American hand be well hidden.”

Despite the Americans’ desire for early results, the Chilean military took its time, but after it finally acted, in 1973, it methodically began “inoculating” Chile against Communism. The extremity of the measures that were employed led the U.S. to suspend military aid to Chile in 1976, however, and relations soured further after the murders of Orlando Letelier and Ronnie Moffit were linked directly to the chief of Chile’s intelligence agency. Pinochet was an embarrassment, and from the Carter Administration onward official U.S. policy was to promote Chile’s “democratization,” by encouraging Pinochet to soften up and permit elections. He did not take kindly to the lectures, and his gruff posturings led one Reagan emissary, Assistant Secretary of State Langhorne Motley, to tell the New York Times that Pinochet was the “toughest nut I’ve ever seen. He makes Somoza and the rest of those guys look like a bunch of patsies.”

In March of this year, Pinochet, dressed in a dove-gray military uniform with red and black accents and gold braid, finally stepped down as Commander-in-Chief of the Chilean Army, a post he had retained after giving up the Presidency, in 1990. At an open-air military ceremony held in his honor, the band played “Lili Marlene,” his favorite song, and he shouted out “Mission accomplished!” and then tearfully handed over his ceremonial sword of office to his successor. The very next day, Pinochet arrived in a business suit at the Congress building in Valparaíso, to be sworn in as senator for life. Thousands of protesters who had gathered in the streets outside were quelled by police armed with tear gas, water cannons, and batons. He was greeted inside the Senate chamber by his supporters and by members of the opposition, some of whom were wearing black armbands and holding up photographs of those who had died or disappeared during the previous twenty-five years. He was in the uncomfortable position of being among his enemies, including Juan Pablo Letelier, the son of Orlando Letelier, and Isabel Allende, both of whom are members of Congress. Fistfights had to be broken up before the swearing-in could proceed, and, despite the resumption of business as usual, the atmosphere inside Chile’s Senate has been close to surreal ever since.

Pinochet’s presence in the Senate (which is in a building he had constructed on the spot where his childhood home once stood) is a reminder that Chile’s democracy is a “tutored” one—tutored by Pinochet. In many ways, the Chilean dilemma is symptomatic of the difficulties confronted by many societies that have emerged from authoritarian rule in the last decade or so. With few exceptions, the usual quid pro quo for the peaceful restoration of civilian rule has been a general amnesty for crimes committed by the ancien régime. But what happens when the ruling military dictator “permits” a return to democracy and, before leaving power, rigs the laws so as to guarantee himself, and the armed forces, an ongoing role in domestic politics?

Thanks to the constitution of 1980, which his regime ushered into law, Pinochet, as a former President, was automatically granted the post of senator for life. He joined nine other constitutionally mandated “designated” senators, including several of his closest former military aides—men like General Canessa—in the forty-eight-member chamber. Together with the elected senators of the two pro-Pinochet right-wing parties, these designated senators form a majority. They have already demonstrated their clout, thwarting three efforts to reform the constitution, which, among other things, gives the military control over its own budget, as well as control over the powerful National Security Council. When Pinochet stepped down as Commander-in-Chief, he named his own successor.

A few weeks after the swearing-in, the current President, Eduardo Frei, responded to widespread public outrage over Pinochet’s new lease on life by going on television to float the notion of a national plebiscite on the constitution. But his speech was most likely a face-saving gesture, since a plebiscite to reform the constitution would require that the constitution itself first be amended in Congress, and that, in turn, would require a majority vote in the Senate. Pinochet has constructed a very clever shelter for himself and his friends.

Isabel Allende acknowledges Pinochet’s legal right to be in the Senate, but, she says, “to see Pinochet dressed in civilian clothes, with the title of senator for life, he who was a dictator, the person responsible for a government which exercised state terrorism—is very shocking for anyone with a democratic conscience.”

Pinochet’s most substantial claim to being a good leader is that he oversaw the Chilean economic miracle. With Congress closed down, and political parties and union activity outlawed, there were no obstacles to the implementation of Milton Friedman’s program of a free-market “shock treatment.” Drastic cuts were made in public spending to cure a hyperinflating economy. Banks were deregulated, interest rates freed, and import tariffs slashed; state-owned enterprises were sold off. In response, the junta obtained lenient refinancing for Chile’s foreign debt and munificent loans from the World Bank, the Inter-American Development Bank, and other financial institutions.

Pinochet made sure that the armed forces received some of the benefits of the flourishing economy. By law, the military receives ten per cent of the profits from the copper industry, Chile’s main export earner, which is still under state control. The nationalization of copper was one Allende measure that was popular across the political spectrum. Copper had been controlled by United States mining interests for decades and was a contentious national-sovereignty issue.

Aside from one major financial crisis in the early eighties, caused by bad investments and overspending, Chile’s economy has grown rapidly. Along with the new foreign investments came credit cards and a robust stock market. Private, employment-linked schemes began to replace state-provided social-security and health-insurance programs; new private schools and private universities were built. Chile today has the largest middle class in Latin America, estimated at sixty per cent of its population; a ninety-five-per-cent literacy rate; low infant mortality; an average life expectancy of seventy-four years; and declining poverty levels.

There are three Chilean billionaires on the Forbes rich list, but, because wages for the poor have not risen along with Chile’s economic growth, the country has one of the worst ratios of income disparity in Latin America—the wealthiest twenty per cent of Chileans earn fourteen times as much as the poorest—and the gap appears to be widening. For the twenty-five per cent of Chileans still living below the official poverty line, the trickle-down benefits of the free-market miracle remain elusive. I visited a slum built along an irrigation canal on Santiago’s dusty outskirts, the result of an organized land “invasion” by poor migrants from rural central Chile. The houses were rudimentary wooden shacks, although they had free electricity, robbed from the power lines that stretched above them, and the dirt streets were laid out in an orderly grid. There was no running water or proper sanitation. Behind each shanty stood a rough latrine made of scrap wood or metal, and some, but not all, had large blue plastic bidones, containers filled with water purchased from the drivers of roving trucks. A dirt lane led out to the main road and people walked along it, or else paid for rides in horse-drawn jitneys.

The prevailing perception among upper- and middle-class Chileans is that the poor, el pueblo, are Communists—“Allende’s people.” When Pinochetistas talk about the “eight per cent” of Chileans who still vote for the Communist Party, they point an accusing finger toward Santiago’s slums. One day, driving with an affluent Chilean woman on the capital’s outskirts—on an excursion that was supposed to lead us to a wine-growing friend’s country house—I took a wrong turn, and we found ourselves in an unkempt area of low-income housing and hardscrabble cayampas. As we got deeper into the población, my passenger became very nervous. Concealing her Louis Vuitton handbag beneath her legs and making sure the car doors were locked and the windows up, she exclaimed, “We should turn around! This is where all the thieves and muggers, the murderers, rapists, and terroristas come from!”

A largewhite rabbit hopped around the lush green lawn of Marco Antonio Pinochet’s back yard, which is separated by a wall from his father’s home on a gated street in the upper-middle-class suburb of La Dehesa. Periodically, his wife ran out, trying to catch the rabbit and put it back in its hutch. In keeping with family tradition, Pinochet’s youngest son is named after a Roman ruler (his elder brother is Augusto, Jr.). He is not interested in government, however, and after a long stint in the United States, learning how to fly helicopters and airplanes, he has become a businessman. When I visited him, on a Saturday afternoon, he and his wife, and some friends—a wealthy Chilean and his wife, Miss Chile of 1980—were relaxing on the Pinochets’ back porch. Their children had been taken off by their nannies to see a movie.

The men discussed whether or not they would bet on a racing tip given to them by a horse trainer. Marco Antonio’s friend, who had recently returned from a visit to Cambodia, told a story about receiving, as a gift, a carved stone frieze plundered from Angkor Wat. Not daring to risk smuggling it out of the country, he had left it behind to be shipped to him. But now he feared that the antiquity would never arrive. The conversation then turned to official corruption in Asia. Marco Antonio noted that many Latin-American governments were nearly as corrupt as those in Asia. “What Latin America needs is authoritarian democracies,” he said. “Corrupt democracies are no good.” He lapsed into thought for a moment, and then added, “But corrupt dictatorships are no good, either.”

Financial corruption is not high on the list of things that Pinochet is accused of, but a congressional panel—determined to find him criminally liable for something—has demanded a sworn accounting of his personal assets. Although his pre-1973 tax returns reflected the typically modest earnings of a Chilean military officer, Pinochet is now believed to own at least five properties around Chile, worth several million dollars. The congressmen want to know how, and with what funds, he obtained them.

In the past, accusations of fiscal impropriety have prompted strong reactions from Pinochet, who prides himself on being a man of simple tastes, and impeccably honest. When a public outcry greeted his use of state funds to build a huge new Presidential mansion in the exclusive hilltop suburb of Lo Curro, Pinochet was mortified, and never took up residence there. Today, the mansion serves as a clubhouse for senior military officers.

In 1984, a Christian Democratic senator, Jorge Lavandero, was nearly beaten to death in the streets of Santiago by thugs when he attempted to pursue a legal inquiry into the low price Pinochet had paid for some government-owned land for a private weekend retreat in the mountains outside Santiago. Lavandero spent six months in the hospital and permanently lost the hearing in his left ear. Pinochet kept the land and went ahead and built his retreat, which is called Melocotón. I visited Melocotón with Lucía Pinochet. Set in a grove of fruit trees in a canyon above the Maipo River, it is a simply built Bavarian-style chalet of cement, wood, and corrugated tin, with small adjoining apartments for the Pinochet children; a swimming pool; and a gymnasium and library for the General. Whatever methods Pinochet used to buy it, it seemed disappointingly modest.

Other financial dealings in the Pinochet family appear to be more egregious. When a scandal erupted in 1990 over the revelation that Pinochet’s elder son, Augusto, Jr., had been paid nearly three million dollars by the Army after it bought a gun factory he owned a small percentage of, Pinochet sent troops into the streets of Santiago to express his displeasure. The investigation was quashed, but when it was reopened three years later he sent out the troops again.

Although Pinochet no longer has the same prerogatives for the use of force to defend his integrity, he is Commander Emeritus for Life of the Army and has at his disposal a contingent of military bodyguards, armored Mercedes-Benzes, and an ambulance, which accompanies him everywhere. These security perks have gone unquestioned, because, as one of his aides, Fernando Martínez, told me, “The General has a great many enemies.” In 1986, a Marxist guerrilla group nearly succeeded in killing him, in a spectacular ambush as he returned from a weekend at Melocotón. Pinochet survived more or less unscathed, but five of his bodyguards died. Four leftists in Santiago were kidnapped and murdered in apparent reprisal.

Pinochet had something of a public-relations triumph late in August this year, when he managed to look like a statesman by negotiating a deal in Congress. Several senators were attempting to abolish the national holiday of September 11th, which the Army has celebrated every year since 1973 to commemorate the successful coup. The day has traditionally been marred by violence, and in August the legislature was deadlocked on the issue. “I could see we were going to end in a tie again,” Pinochet recalled when we met. “A path had to be found to break the impasse. We military men always think like that—how to break the impasse. And there was a way out.”

The way out, as he told it, was to propose a compromise with the president of the Senate, Andrés Zaldívar, a Christian Democrat he had once sent into exile. If Zaldívar could muster support on his side, Pinochet would prevail upon the opposition to cast down the eleventh after this year, as long as it was replaced by a new holiday, a Day of National Unity, to be held on the first Monday of every September. After some haggling, Zaldívar agreed; both men went to work on their fellow-politicians, and a few hours later the deal was struck. Ignoring parliamentary protocols, Pinochet walked across the Senate floor, ascended the raised stage where Zaldívar sits, and, after giving him a manly abrazo, sat down in the chair next to him. To the exasperation of his opponents, Pinochet not only had stolen their initiative but had demonstrated his political clout in the Senate and, most gallingly, had managed to present his action as a magnanimous gesture of national reconciliation.

Was this the result he had hoped for? I asked.

“Look,” he replied. “I’m an old man now. I don’t have any greater ambitions in my life. Everything I do, I do for my country. At this time I feel I have shown an attitude of reconciliation, but I don’t see reconciliation coming from the other side.”

What Pinochet was angling for, I guessed, was a political deal to protect him and other former members of his regime from liability for human-rights violations. Although they are partially protected by a retroactive amnesty decreed by the junta in 1978, there are loopholes in the law, and in recent years two of Pinochet’s former military aides have been convicted of offenses not covered by the amnesty. Since Pinochet stepped down as the head of the Army, the number of human-rights suits has increased. Nine criminal lawsuits have recently been filed against Pinochet himself. One of them, brought by a former congresswoman, María Maluenda, charges him with responsibility for the murder of her son, a Communist whose throat was slit in 1985 after he was abducted by soldiers. Another, charging him with “genocide and illegal appropriation of property,” was filed by the Communist Party secretary-general, Gladys Marín, whose husband “disappeared.” Pinochet refuses to acknowledge personal liability for any of the incidents and has stated repeatedly that he can’t be held responsible for what his subordinates may have done.

“The criticisms of me are about things, many times, which I was unaware of,” he says. “Many times I knew when it was too late. And all of those things which I thought were delicate I relayed to the courts. There were abuses on both sides. One day, they killed eleven of my carabineros with a bomb. Another day, they killed a naval officer. . . . So I say, ‘So you suffered a lot. Well, and my people, didn’t they suffer at all?’ Human rights! I say there has to be human rights for both sides.”

This isn’t how Pinochet used to respond to criticisms of his record on human rights. A few years back, when searchers discovered more than a hundred victims of military executions, doubled up in coffins in a mass grave, Pinochet joked darkly, “Whoever buried them served the Fatherland well, by saving money on nails.” This sort of remark makes it hard to refurbish Pinochet’s reputation. “It’ll be a long time before Chileans see him as a grandfatherly figure,” Ambrósio Rodríguez, a close former aide, acknowledges. “It must be hard for him, knowing that half the nation hates his guts.”

Supporters of Pinochet think that the criticism is unreasonable. “The only people persecuted were those who acted outside the law,” the industrialist Hernán Briones says. Briones claims that Pinochet’s “bad image” is due to disinformation spread by leftist Chileans who fled abroad after the coup. General Canessa agrees. “They say General Pinochet should tell where the desaparecidos are,” he says with exasperation. “It’s as though they thought General Pinochet has got a book like this one”—with a flourish, Canessa opens a book on his desk—“and he can look at it and say, ‘Lucho Zapata. Zapata is . . . the people are buried in such-and-such a place.’ How is a head of state supposed to know about this matter?”

In September, a few days before the twenty-fifth anniversary of her father’s death, Isabel Allende organized a concert, “Con Allende Siempre”—“With Allende Forever”—at the National Stadium. It was a benefit for the Allende Foundation. The stadium was a special place, she told me: not only was it where the era of repression under Pinochet began but—and, to her, more important—it was where her father celebrated his 1970 election victory.

I went to the concert at the invitation of Miguel Orellana Benado, a man in his early forties, who teaches philosophy. He is a distant relative by marriage of the Pinochets, and Salvador Allende was a friend of his family’s. Santiago is a small town. After the coup, his family gave refuge to a woman widely believed to have been Allende’s confidante and lover. The military were hunting for her, and the teen-age Miguel was given the task of driving the fugitive around the city in his father’s Mercedes. In the bizarre circumstances of post-coup Chile, this was considered safer than keeping her in their house. Afterward, Orellana was sent abroad, and he spent the next dozen years in voluntary exile, studying in Israel, Sweden, Spain, London, and, finally, Oxford, where he wrote his Ph.D. thesis on the “philosophy of humor.” He returned to Chile in the mid-eighties, and spends several days each week in the old seaside resort town of Viña del Mar, where he teaches at Valparaíso University. His parents also left Chile after the coup, but they never returned. Today they live in Madrid, where, he says, they have made new lives for themselves. At their age (they are in their eighties), he explains, there is little to come back for; most of their friends have died, and the Chile they once knew is long gone.

The scene outside the stadium was like a sixties-revival party. Long-haired kids and bearded leftists in tie-dyed shirts, red-and-black scarves, and Che Guevara T-shirts mingled with hawkers selling Che and Allende memorabilia. Mounted carabineros watched the concertgoers stream into the stadium, which soon was packed close to capacity. Perhaps seventy thousand people filled the bleachers and the field. The smell of pot wafted around; in the stands, members of the Communist Youth organization held up a banner saying “We didn’t betray Allende.” Another sign protested the charging of admission to the show. There was a huge banner with Allende’s bespectacled face printed on it above the stage.

At one point, in between performances, the sound of machine-gun fire filled the stadium, and then several giant video screens showed black-and-white footage of the bombing of La Moneda. Over the din of the attack Allende’s crackling last words, the defiant message he had recorded that day before he died, were heard on loudspeakers. As the audience watched the jets scream in again and again and the palace burst into flame, the enormity of what had happened hit home, and everyone began screaming, over and over again, “Asesino! Asesino!” “Murderer! Murderer!” It was their name for Augusto Pinochet.

A few weeks after I left Santiago, I met Pinochet in London, where he was having some medical checkups. He was staying in one of the modern five-star hotels on Park Lane favored by well-heeled Europeans, Arabs, and Americans. Lucía Pinochet, who was travelling with her father, had warned me that he was not feeling well and had cut back on his activities in London. He hadn’t called his friends; even his tea with Margaret Thatcher had been scratched. In a few days, she said, he was to see a doctor about a hernia. She hoped it could be operated on, but the prognosis did not seem good. Because of her father’s age, Lucía told me, they were afraid to put him under anesthesia: “Nobody wants to take responsibility when the patient is someone important.”

Pinochet was in a good mood, and after we talked for a while he set off to visit Madame Tussaud’s, for the umpteenth time; the British National Army Museum; and then to lunch at Fortnum & Mason. He bought some books about Napoleon, and was delighted when, during a stop at Burberry’s, the head salesman recognized him and was courteous. The next morning, over coffee in an empty lounge at Pinochet’s hotel, I asked him to clarify what exactly he had meant when he told me in Santiago that he was expecting a gesture of reconciliation from his Senate opponents. “Reconciliation has to come from both sides,” he said.

“Yes, but what kind of gesture is it you’re looking for?” I asked.

“A gesture!” he shouted hoarsely. When I repeated the question, he exploded: “To put an end to the lawsuits! There’s more than eight hundred of them. Including some cases that have already finished, but they reopen them again. They always go back to the same thing, the same thing.”

Over the last twenty years, hundreds of cases have been brought against members of the military and intelligence services. Most of them have been dropped, and Pinochet has never had to appear in court. But this may change. Lucía Pinochet told me that in the judicial investigation into the killings of the four men after her father’s near-assassination in 1986 troubling new evidence of official complicity had emerged. “It now seems they were murdered,” she said, “not killed in an armed confrontation, which is what his men told him.” She said that she had been with her father when he was informed by an aide about the incident. He had asked, “What happened to our guys?” “No casualties, mi General,” the aide replied. According to Lucía, Pinochet had looked surprised, and asked, “None?” The answer, again, was “No.” Lucía told him that the story sounded suspicious to her, but he had shrugged and said, “Well, that’s what they say,” and that was the end of it.

Lucía said she was telling me this so that I could understand that her father had been “harmed” by his officers, who “isolated him” and “didn’t always tell him the truth about things, so as to make themselves look better, or to cover things up.” It had always frustrated her, she said, that he seemed to give more credence to what his aides told him than to what she said. In her doting daughter’s way, what Lucía wanted me to believe was that her father was guilty only of naïveté, and of trusting his men too much.

Lucía told me that her father’s visit to London might well be his last. His physical problems were catching up with him. Besides, things weren’t the same in London. People didn’t seem to recognize him anymore. The Burberry’s salesman was an exception. She was hoping he would feel well enough, after his medical examination, to come with her to Paris, to visit Napoleon’s tomb.

History, and Pinochet’s fascination with it, featured heavily in our talks. He expressed his admiration for Napoleon and for the Romans, and we also discussed Fidel Castro, whom he seemed to respect for standing up for his beliefs, and for being a “nationalist.” When it came to Mao, too, he seemed curiously uncritical. He described a visit to Mao’s tomb, and his voice fell into a dramatic hush: “They took me to a large temple, immense, how can I tell you? Like the American Congress building. Where, every day, thousands of people take flowers to Mao. I went to that temple, but Mao isn’t there. Mao is in a second temple further on, where all the walls are of black marble. In the middle is Mao’s catafalque. What a monument!—of silence. Dark . . . half-light, and the catafalque.”